Introduction

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has evolved into an indispensable tool in the evaluation and management of pancreaticobiliary diseases. Over 40 years ago, EUS was developed as a radial scanner, providing circumferential views of the gastrointestinal mucosa and surrounding structures. Comprehension of this type of imaging was akin to axial views of computed tomography (CT) scans and was widely accepted. In the 1990s, linear array echoendoscopes were developed, which provided the ability to obtain biopsies and perform other interventions. While conceptually more difficult to learn, linear EUS has become the main modality for pancreaticobiliary assessment, particularly when an intervention such as biopsy or drainage is required. It is crucial for the trainee endoscopist to have a sound understanding of abdominal anatomy, probe handling, and interpretive skills.

This review provides a practical framework for performing pancreaticobiliary EUS from the perspective of an interventional endoscopist, focusing on scope manipulation to achieve optimization of the image, anatomical landmarks, and identification of pathology.

Intubation of the Esophagus

The tip of the echoendoscope is rigid, nonbending, and relatively long with the ultrasound transducer positioned in front of the optical lens on radial and linear devices. The large knob of the scope is used to deflect the scope tip past the base of the tongue and into the hypopharynx where subsequent straightening eases passage. Inflating the balloon of the echoendoscope, if one is utilized, provides some cushioning as it penetrates the cricopharyngeus, and this can be done before advancing the scope into the mouth if needed. Similar to passing a duodenoscope, the endoscopic view is limited. However, a rule of thumb is that if the vocal cords are seen on the screen, the tip of the echoendoscope is in line with the esophagus and may be advanced. Slight rotation of the probe allows the echoendoscope to enter the proximal esophagus. It is essential to avoid pushing against fixed resistance to reduce the risk of a perforation.

A Station Approach to the Examination

Gastroesophageal Junction (GEJ)

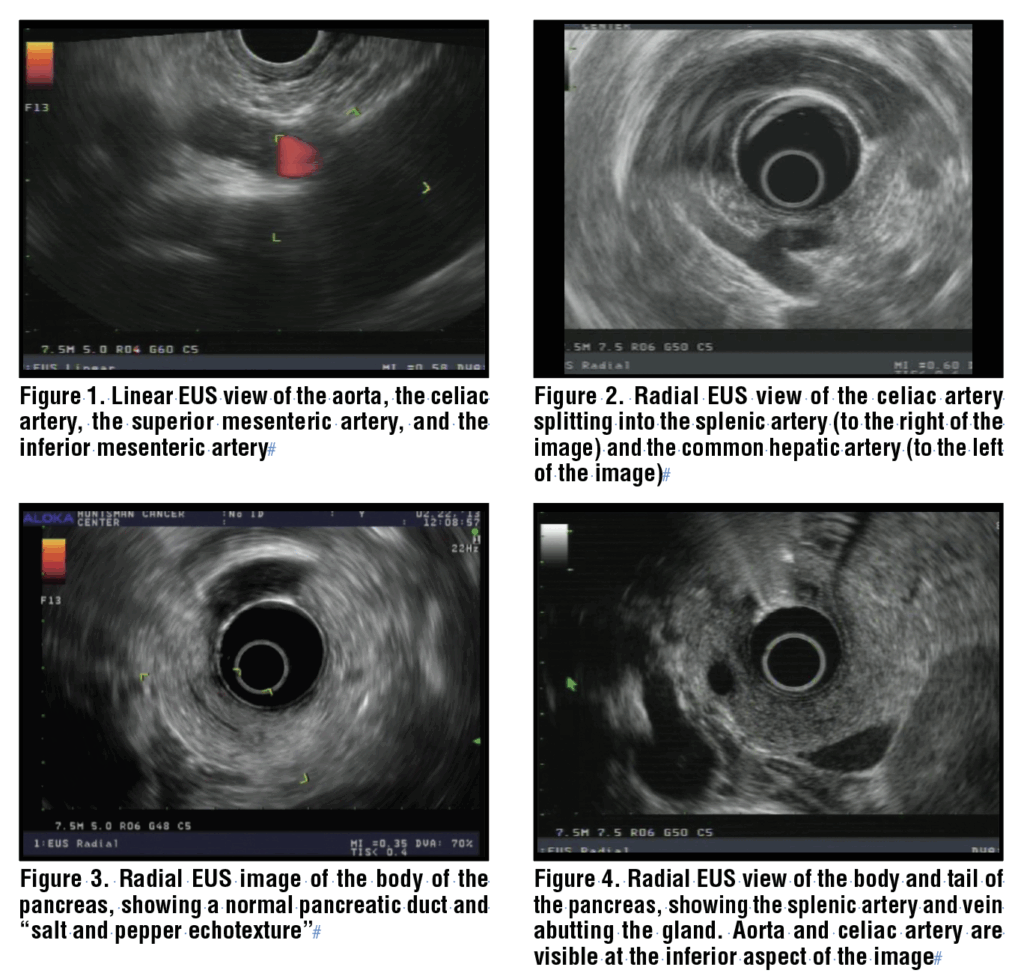

With the echoendoscope positioned just distal to the squamocolumnar junction, the abdominal aorta is readily identified by applying clockwise torque to the shaft of the scope. With the linear echoendoscope, the aorta appears as a long, anechoic structure, often with hyperechoic walls, sloping down from right to left across the monitor with the pleura of the left lung clearly seen below the vessel wall. The diaphragmatic crura are seen, and when the echoendoscope is advanced further, the celiac artery is identified as it is the first vessel branching off the abdominal aorta. The superior mesenteric artery is located just below it, and the inferior mesenteric artery is also easily seen below that. (Figure 1) The echoendoscope should be gently torqued clockwise and counterclockwise to visualize these structures.

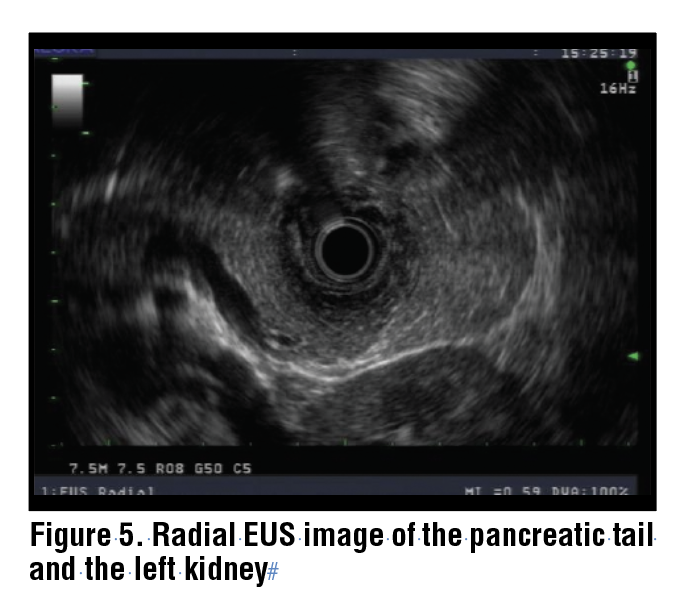

The celiac artery can be followed until it branches into the splenic artery and the common hepatic artery. (Figure 2) At that point, advancing the echoendoscope another 1 to 2 cm and deflecting the scope tip down (thumb up, dial moves “away”), the pancreas and confluence of the portal vein should come into view. If this is not achieved because of a hiatal hernia or other anatomic variant, another approach is to advance the echoendoscope into the body of the stomach, to about 50 cm from the incisors. Gentle withdrawal of the echoendoscope with simultaneous clockwise torque will often allow the body of the pancreas to come into view.

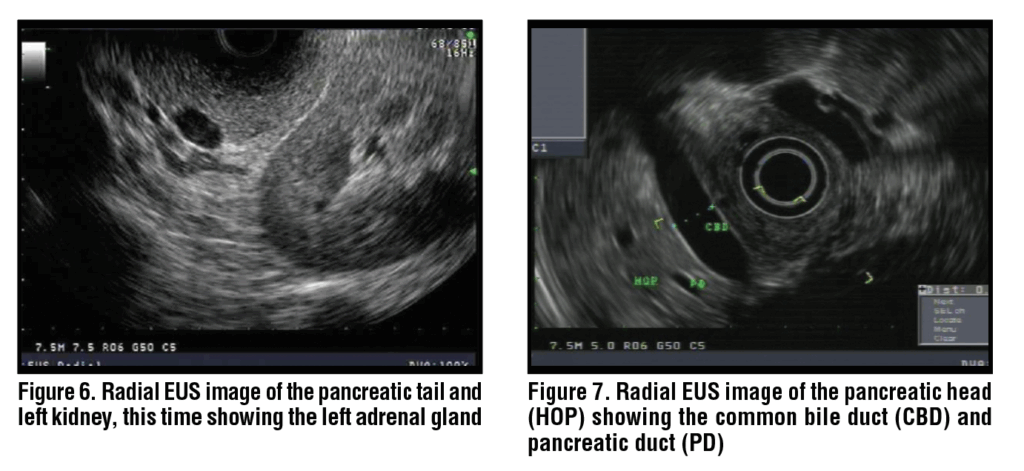

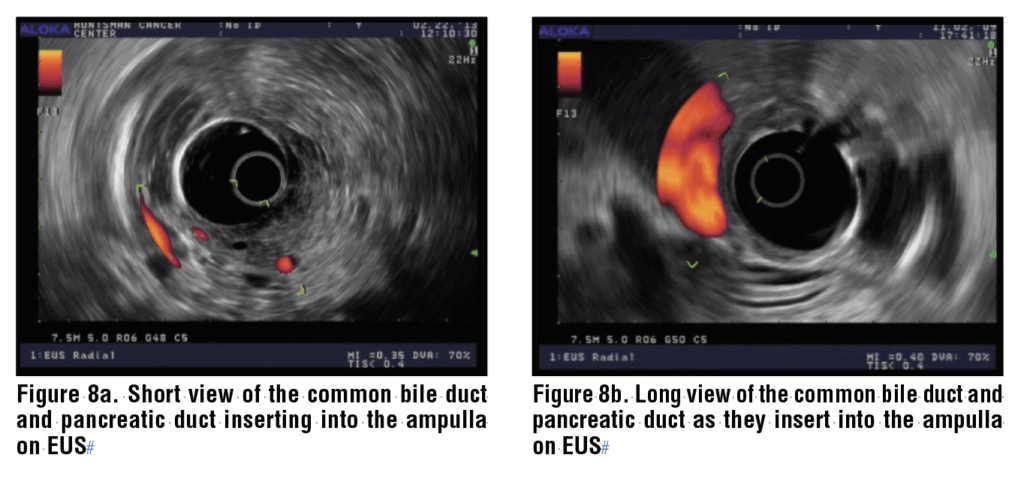

The body of the pancreas is identified by its characteristic “salt and pepper” appearance, as well as the presence of the splenic artery and vein. (Figure 3) The splenic artery and vein can be confirmed by pulse wave doppler based on flow patterns, and in general the splenic artery is narrower than the vein and follows a more tortuous course. In the body of the pancreas, the splenic artery and vein are seen as two anechoic circles, and the main pancreatic duct is positioned to the left of these on the monitor. (Figure 4) From that position, the echoendoscope may be gently torqued clockwise and withdrawn to keep the pancreatic duct in view and to scan the body and tail of the pancreas. During this maneuver, the left kidney is identified and acts as a guide to the demarcation of the junction between the body and tail. (Figure 5) The splenic artery and vein may be traced with further withdrawal to the splenic hilum and spleen. With minor counterclockwise torque, the left adrenal gland is also identified as a sprawling “longhorn steer-shaped” structure. (Figure 6)

From the body of the pancreas, with the splenic artery and vein in view, the rest of the body of the pancreas and genu may be visualized by counterclockwise torque and gentle advancement of the scope. In children or in very thin adults, the pancreatic head can often be seen from the stomach but this is not typical for normal sized adults. The pancreatic duct may be traced across the portal confluence as it dives down into the head.

Generally, the next step in the station-based evaluation is to advance the echoendoscope to the duodenal bulb. However, another option for evaluating the common bile duct and head of the pancreas from the GEJ involves executing an “alpha maneuver.”1 Starting at the GEJ and the scope in the anticlockwise position, the left lobe of the liver is identified and the scope is rotated clockwise 90 degrees. The inferior vena cava, hepatic veins, and potentially the liver hilum are brought into view. By pushing the scope inferiorly 2 cm, the portal vein, hepatic artery, and common hepatic duct (CHD) are seen. The gallbladder and cystic duct may also be seen inferior to the CHD. The portal vein and common bile duct (CBD) may be traced with a downward and gentle clockwise-counter-clockwise rotation until the head of the pancreas and portal confluence is identified. The rest of the pancreatic head and CBD are identified with further clockwise rotation and tip deflection.1 This is an important technique, particularly in the setting of gastric outlet obstruction or altered anatomy, when the duodenum is not accessible for the station approach to pancreaticobiliary imaging.

Duodenal Bulb

The echoendoscope is advanced to the antrum of the stomach and through the pylorus. It may be helpful to insufflate the balloon of the scope with a small amount of water to provide a cushion for the stiff scope tip as it enters the duodenal bulb. The tip of the linear echoendoscope is approximated to the apex of the duodenal bulb, with the scope tip deflected upward (thumb down). This is often referred to as “wedging” the echoendoscope in the duodenal bulb. Gentle counter-clockwise rotation will reveal the head of the pancreas. A main landmark is the portal vein, confirmed by the use of color Doppler. Between the transducer and the PV, the CBD is identified along with the PV. The CBD will be closer to the transducer than the PD. (Figure 7) The CBD can be traced into the liver with counter-clockwise torque, and through the head of the pancreas to the ampulla with clockwise rotation. The main pancreatic duct is also identified in the head of the pancreas, and it can also be traced to the ampulla with rightward torque. This position is the most common site for sampling masses in the head of the pancreas and is also the most critical for assessing biliary stone disease in the CBD or CHD.

Ampulla

The echoendoscope is advanced to the second portion of the duodenum and reduced, similar to an ERCP scope. During withdrawal, the major papilla is identified endoscopically.

Once identified endoscopically, the tip of the scope is deflected upward such that the transducer is nestled perpendicular to the papilla. The transducer is gently rotated clockwise, and the ampulla with common bile duct and pancreatic duct in a linear orientation come into view. Anticlockwise rotation will allow the operator to look up towards the proximal biliary tree. The ampulla appears as a thickened, hypoechoic, homogeneous structure within the duodenal wall but projecting outward towards the lumen, with the bile duct appearing more superficial or close to the transducer (given the intraduodenal nature of the distal common bile duct), and the pancreatic duct deeper. (Figures 8a and 8b) The pancreatic duct and common bile duct may form a common channel is they enter the major papilla, or they may arrive with distinct orifices, each surrounded completely by sphincter tissue. The echoendoscope is slowly withdrawn and rotated clockwise and counterclockwise until the portal confluence is identified.

In the setting of pancreas divisum, the ventral pancreatic duct will be seen entering the ampulla, but it will appear short and truncated. The dorsal pancreatic duct will be unable to be identified merging into the main pancreatic duct and may be identified merging into the duodenal wall at the minor papilla.

Second and Third Portion of the Duodenum

For imaging the uncinate process of the pancreas, the echoendoscope is advanced just distal to the major papilla. With rotation of the scope clockwise and counterclockwise, the aorta is identified, often running vertically along the left-hand side of the EUS image, with the IVC appearing parallel to it. Upon identification of the aorta, the shaft of the scope is generally rotated clockwise and slowly withdrawn. The uncinate identified, and with further gentle scope withdrawal and torquing, the examination of the pancreas is completed. The dorsal anlage of the pancreas comprises the anterior and superior portions of the head and extends into the neck, body, and tail. It is typically more homogeneous and hyperechoic compared with the ventral anlage. The ventral anlage, derived from the ventral pancreatic bud, is located in the posteroinferior aspect of the pancreatic head and uncinate process, and appears more heterogeneous than the dorsal anlage. It is usually more hypoechoic and lobular. It is important to recognize these normal embryologic differences so that the ventral anlage is not mistaken for changes of chronic pancreatitis or neoplasm.

Identification of Pathology

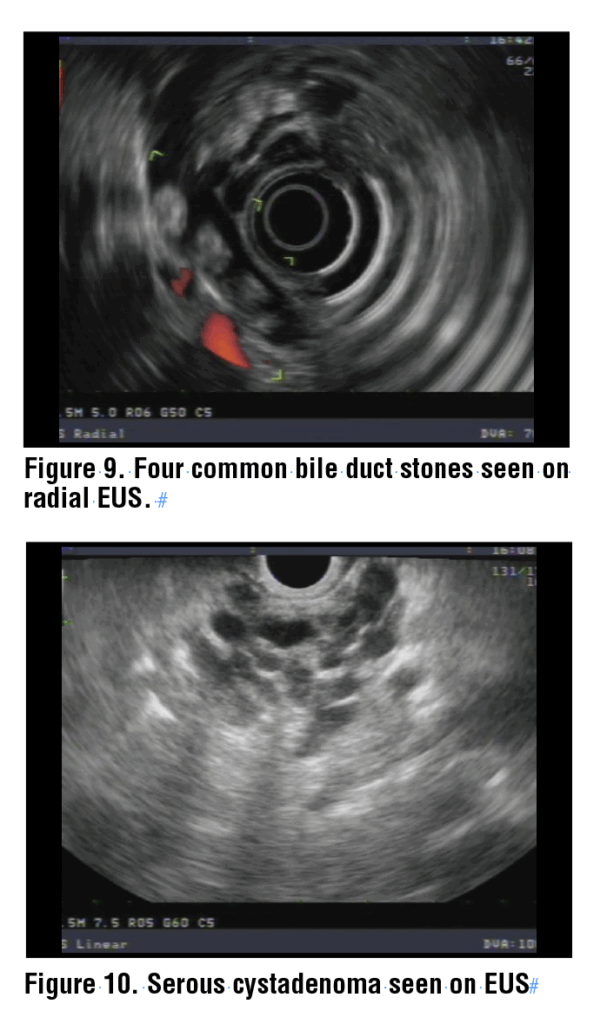

Among the most common indications for pancreaticobiliary EUS are suspected choledocholithiasis and solid or cystic lesions of the pancreas. The best location to identify stones in the bile duct is with the echoendoscope in the duodenal bulb. From this viewpoint, the portal vein and common bile duct are identified and can be traced cephalad to the liver and down to the ampulla. The view from the ampulla may also identify distal stones. Stones in the bile duct appear as round, oval, or triangular hyperechoic structures that typically have post acoustic shadowing. (Figure 9) Shadowing represents a disruption in the sound waves by a dense structure, causing a dark, echo-free image beyond the structure. Occasionally, soft stones or sludge will not create a shadow, but must be accurately identified regardless.

The appearance of pancreatic lesions is dependent on the nature of the mass. Cystic lesions may appear as anechoic structures that may or may not have a wall and/or septations. Side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) may sometimes be identified as communicating with the main pancreatic duct. Main duct IPMNs appear as either diffuse or focal dilation of the main pancreatic duct. Serous cystadenomas are typically multiseptated, with a sponge-like appearance, with a “central scar,” which appears as a bright structure within the cyst. (Figure 10) Mucinous cystic neoplasms are often unilocular and appear most commonly in the body and tail of the pancreas. Solid pseudopapillary tumors typically appear as well-defined, mixed solid and cystic lesions that are hypoechoic and often with a hyperechoic rim. Pancreatic pseudocysts are generally located adjacent to the pancreas, are often left of the midline, and may become very large, compressing adjacent organs and vessels, and they may (rarely) have septations. They often appear anechoic, but in the setting of infection or necrosis, may appear more hypoechoic as opposed to anechoic. Organized necrosis within the pseudocyst appears hyperechoic.

Solid masses include neuroendocrine tumors, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, and metastatic lesions. Neuroendocrine tumors may be solid, mixed, or cystic, thereby complicating diagnosis. If solid, they are generally well-defined, hypoechoic, homogeneous lesions. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is identified as a hypoechoic area, sometimes poorly defined, often with shadowing due to the density of the tissue or the presence of calcifications. Metastatic lesions are either isoechoic or hypoechoic and well-defined.

EUS is also used to diagnose chronic pancreatitis using a variety of changes related to the parenchyma and ducts. Parenchymal changes include calcifications, lobularity, hyperechoic strands and foci, cysts, and honeycombing. Ductal changes include calcifications within the duct, ductal dilation and ectasia, visible side branches, and hyperechoic duct margins. Objective grading systems such as the Rosemont Criteria are often applied when considering a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.2

EUS-Guided Tissue Sampling of Solid Pancreatic Lesions

The ability to biopsy solid lesions in the pancreas and surrounding areas is one of the key skills of linear-based endosonography. Additionally, EUS-guided sampling of pancreatic parenchyma may be helpful in diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis. Previously, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needles were used in conjunction with rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) for sampling of solid lesions, particularly in the pancreas. With the advent of newer, fine-needle biopsy (FNB) needles, the need for ROSE has significantly diminished.3 Current society statements recommend the use of end-cutting FNB needles over reverse-bevel FNB or FNA needles. 4,5,6Additionally, the routine use of ROSE for solid pancreatic masses is not recommended.5

The fanning technique, whereby the needle is moved in multiple directions within the lesion during each pass using deflection of the large (up-down) wheel, is recommended by some authors as it improves diagnostic accuracy and adequacy of tissue sampling.7 Additionally, 19- and 22-gauge needles are often suggested over 25-gauge needles, as they may result in higher-quality specimens that are more likely to be adequate for personalized medicine and ancillary molecular testing.5,8 However, in cases where the endoscope is severely torqued and there is limited maneuverability, or when the 22-gauge needle does not penetrate the lesion, the 25-gauge needle is an acceptable option.

Conclusion

The approach to pancreaticobiliary linear EUS anatomy outlined here helps learners establish a framework for completing their exams using a systematic approach. As experience is gained, each endosonographer will develop their own modifications of these methods to achieve optimal imaging and assessment of the pancreaticobiliary anatomy.

References

References

1. Dhir V, Adler DG, Pausawasdi N, Maydeo A, Ho KY. Feasibility of a complete pancreatobiliary linear endoscopic ultrasound examination from the stomach. Endoscopy. Jan 2018;50(1):22-32. doi:10.1055/s-0043-118592

2. Catalano MF, Sahai A, Levy M, et al. EUS-based criteria for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis: the Rosemont classification. Gastrointest Endosc. Jun 2009;69(7):1251-61. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.043

3. Dbouk M, Davis BG, Peller M, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle biopsy sampling of solid pancreatic masses with and without rapid onsite evaluation for commercial next-generation genomic profiling. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 21 2025;doi:10.1016/j.gie.2025.03.1208

4. Facciorusso A, Arvanitakis M, Crinò SF, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue sampling: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical and Technology Review. Endoscopy. Apr 2025;57(4):390-418. doi:10.1055/a-2524-2596

5. Machicado JD, Sheth SG, Chalhoub JM, et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of solid pancreatic masses: summary and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. Nov 2024;100(5):786-796. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2024.06.002

6. Gkolfakis P, Crinò SF, Tziatzios G, et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of end-cutting fine-needle biopsy needles for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. Jun 2022;95(6):1067-1077.e15. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.01.019

7. Lee JM, Lee HS, Hyun JJ, et al. Slow-Pull Using a Fanning Technique Is More Useful Than the Standard Suction Technique in EUS-Guided Fine Needle Aspiration in Pancreatic Masses. Gut Liver. May 15 2018;12(3):360-366. doi:10.5009/gnl17140

8. Tomoda T, Kato H, Fujii Y, et al. Randomized trial comparing the 25G and 22G Franseen needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition from solid pancreatic masses for adequate histological assessment. Dig Endosc. Mar 2022;34(3):596-603. doi:10.1111/den.14079

Jennifer L. Maranki

Jennifer L. Maranki Douglas G. Adler

Douglas G. Adler