Dermatologic findings are common in liver disease, and may represent the very earliest or most prominent signs of an underlying disorder. While most practitioners recognize jaundice as a sign of hepatobiliary disease, there are numerous cutaneous signs which can point to concomitant liver dysfunction. Additional signs of liver disease may include findings like disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis or Terry’s nails in cirrhosis, or porphyria cutanea tarda in hepatitis C. It is important for general practitioners and dermatologists alike to be able to recognize and describe such lesions, as identification of cutaneous manifestations of liver disease can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment initiation for patients. In this article, we present the spectrum of typical associated cutaneous findings of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and cirrhosis.

Introduction

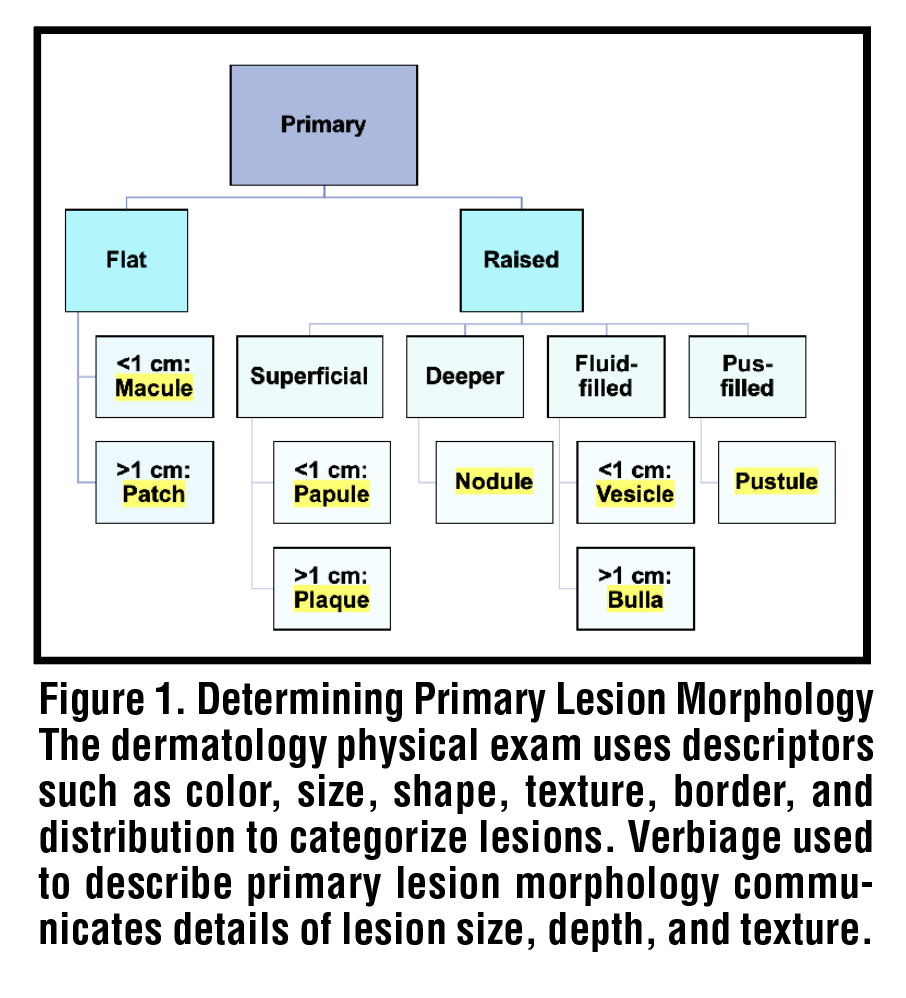

Chronic liver disease is a preeminent cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for nearly two million deaths annually.1 In the United States, 4.5 million adults aged eighteen or older have been diagnosed with liver disease, and the most recent CDC summary data lists chronic liver disease and cirrhosis as the 10th leading cause of death nationally.2,3 Total expenditures related to chronic liver disease exceeded $32.5 billion in 2016 and continue to rise, driven primarily by acute care spending.4 Extrahepatic manifestations of liver disease are numerous, and include effects on the gastrointestinal, nervous, endocrine, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and hematological systems as a result of the liver’s diverse functionality.5 However, the very earliest and most prominent presenting signs of underlying liver dysfunction often lie in the skin.6 Dermatologic manifestations of liver disease are common and may be readily identified in a non-invasive manner via the physical examination. In this review, we present the spectrum of specific and non-specific cutaneous findings in hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and cirrhosis. We discuss lesion description including pattern and morphology [Figure 1], lesion etiopathogenesis and significance, and briefly describe relevant steps for management of dermatologic lesions.

Cirrhosis

Spider Angiomata

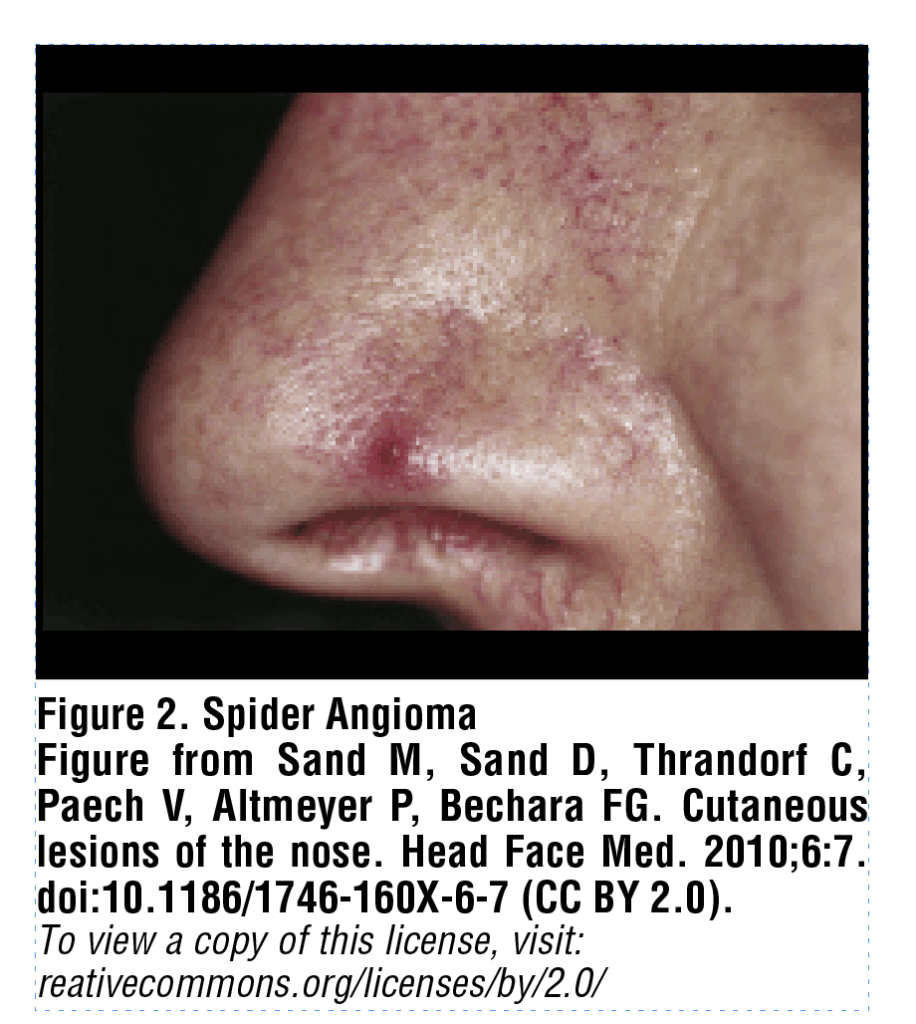

Spider angiomas are superficial groups of dilated blood vessels, blanchable with pressure, most often appearing on the face or upper trunk. A spider angioma can be described as a central red papule (arteriole) with fine, tortuous vessels extending radially outward in a stellate pattern [Figure 2]. These lesions are considered to occur in elevated estrogen states, such as cirrhosis, though recent studies have also examined the role of serum vascular growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF).7 Li et al. demonstrated that increased plasma levels of VEGF and bFGF were the most significant predictors for the presence of spider angiomas in a sample of 86 cirrhotic patients, indicating that neovascularization may play a key role in their pathogenesis.8 Multiple spider angiomas are characteristic of chronic liver disease with a specificity of 95% and, in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease, act as a predictor of increased risk for both esophageal varices and hepatopulmonary syndrome.6,9 Spider angiomas require no treatment, however fine-needle electrocautery, 585nm pulsed dye laser, 532nm KTP (potassium-titanyl-phosphate) laser, or electro-desiccation can be used to remove spider angiomata for cosmetic purposes.

Paper money skin

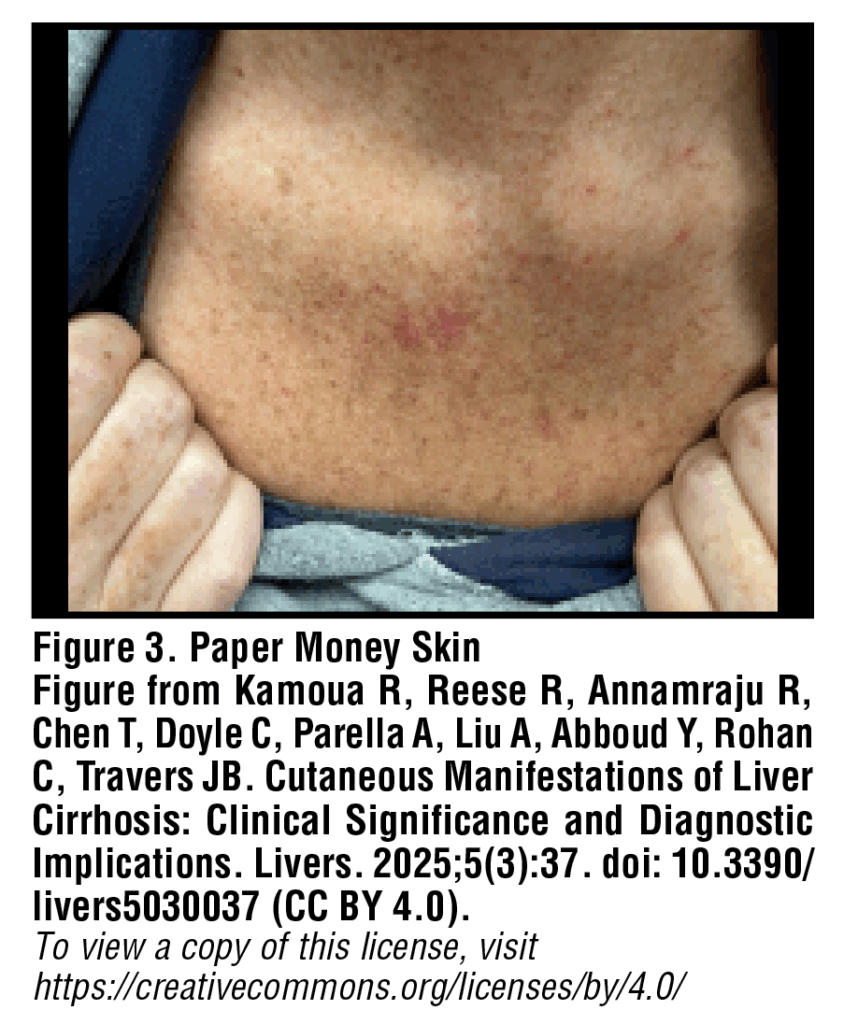

Paper money skin, or “dollar paper markings”, is a common yet often overlooked finding in patients with cirrhosis. These lesions appear as diffusely scattered, threadlike, superficial capillaries which can look similar to spider angiomas and involve a similar pathogenetic process [Figure 3]. In contrast to spider angiomas, paper money skin lesions are described as short, randomly scattered telangiectatic vessels which occasionally coalesce into irregular annular patches.10 The finding of paper money skin is most often observed in cases of cirrhosis related to chronic alcohol use, with lesions typically appearing first on the upper trunk. No treatment is required for paper money skin, however case reports have noted a disappearance of these lesions in patients undergoing hemodialysis.11

Palmar Erythema

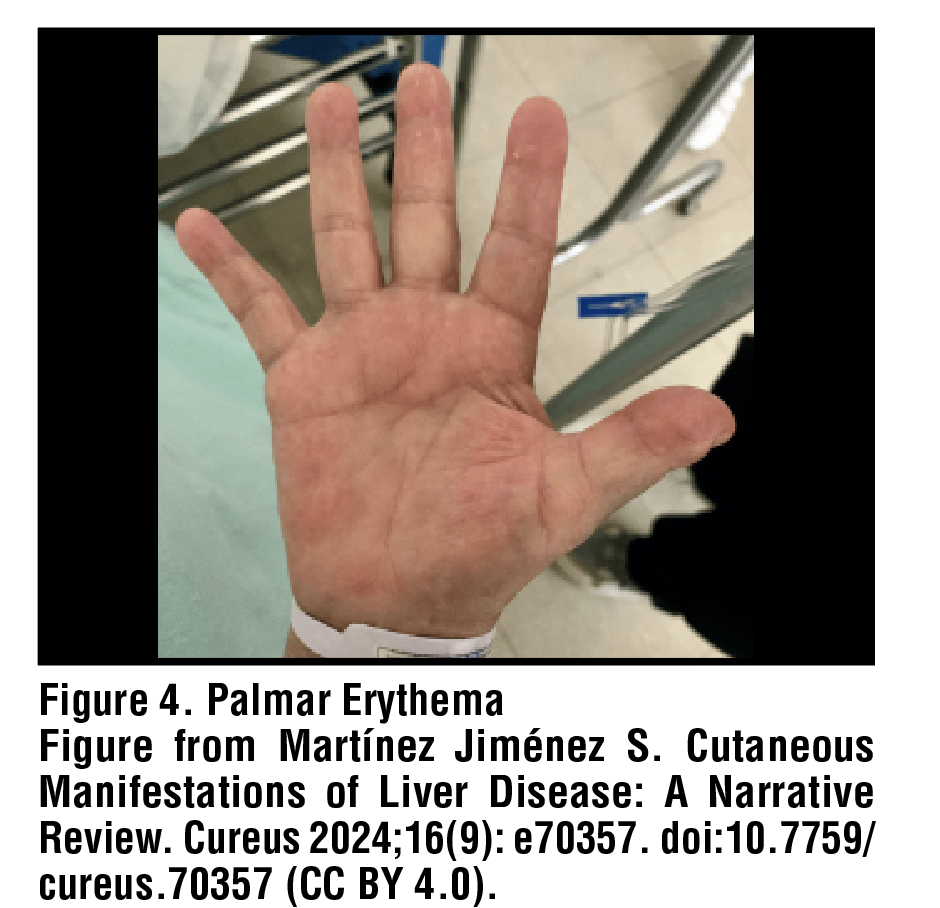

Of all patients with cirrhosis, approximately 23% will develop palmar erythema. Palmar erythema presents as a symmetrical, blanchable redness of the palms and fingertips, which may localize to the thenar and/or hypothenar eminence [Figure 4]. The degree of erythema is often related to the severity of the underlying condition, such that increasing redness indicates worsening disease. While the precise pathogenesis of this finding remains unknown, patients with cirrhosis likely develop palmar erythema secondary to local vasodilation from hyperestrogenemia. In addition, plasma prostacyclins and nitric oxide have also been posited to play a role.12,13 No treatment is indicated for palmar erythema, and management of underlying cirrhosis may or may not lead to improvement.

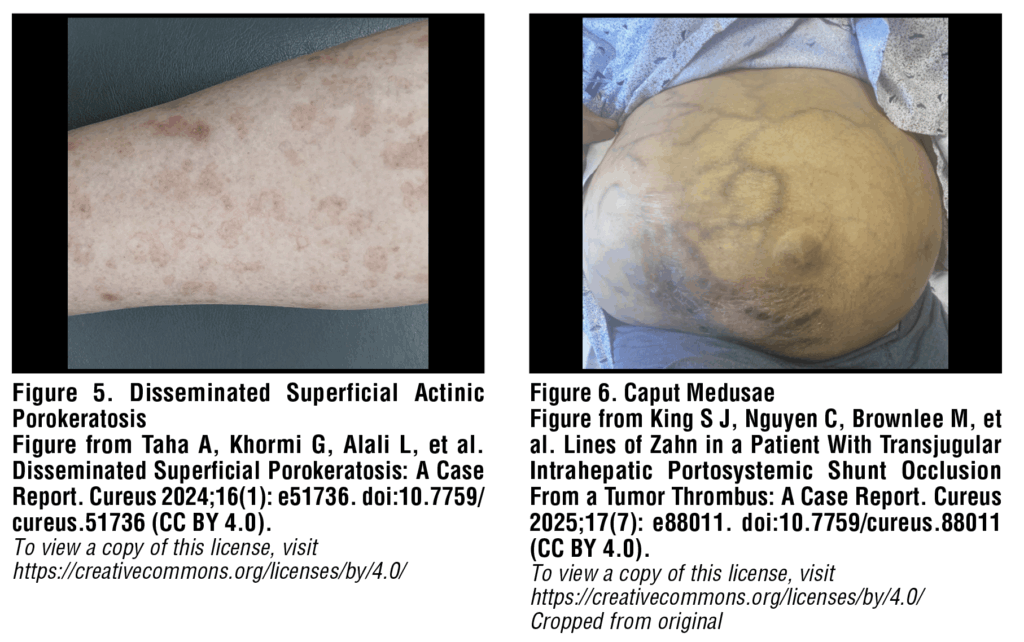

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is a keratinization disorder that causes discrete dry patches to form in clusters on sun-exposed areas of the lower arms and legs. Lesions are pink-brown annular or polycyclic macules and plaques with raised keratotic borders [Figure 5]. Patients with cirrhosis related to alcohol use are more prone to developing DSAP than the general population. DSAP has numerous documented triggers including sun exposure, phototherapy, and infection, though immunosuppression is widely considered a primary cause of onset.14 Given that cirrhosis is associated with several abnormalities of innate and adaptive immunity, it logically follows that porokeratosis could be triggered by immunosuppression due to liver cirrhosis. With regards to management, it is important to note that, while uncommon, squamous cell carcinoma can develop within DSAP lesions. For this reason, patients with DSAP should be referred to a dermatologist for examination and counseled regarding proper sun protection. Treatment for DSAP is varied and includes options such as topical 5-fluorouracil, cryotherapy, moisturizers to reduce dryness and irritation and, most promisingly, topical 2% lovastatin with or without topical cholesterol.15

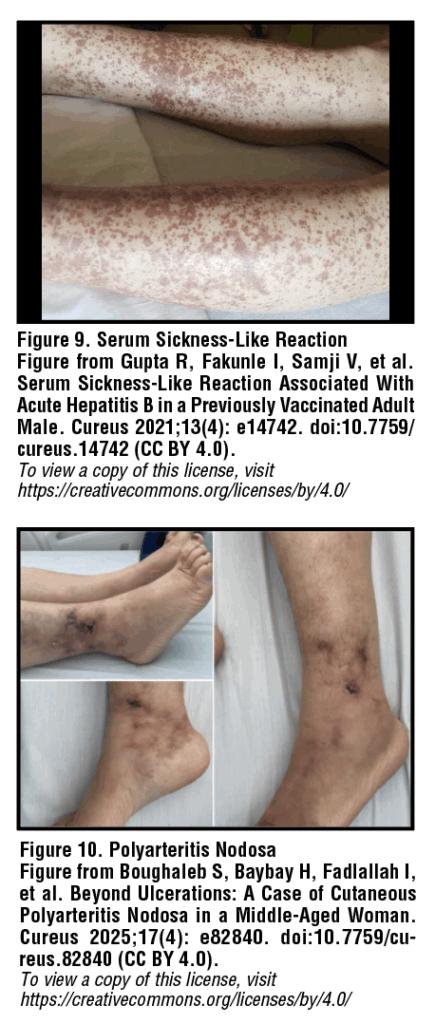

Caput medusae

Severe portal hypertension as a result of cirrhosis leads to portosystemic collateral formation in the form of esophageal, gastric, rectal, and abdominal varices.16 Paraumbilical abdominal wall varices are termed “caput medusae” or “head of Medusa”, referencing their likeness to the mythological Greek gorgon with snakes for hair. These collaterals form as a result of backflow from the left portal vein, through the paraumbilical veins, to the periumbilical systemic veins within the abdominal wall. Caput medusae are often described as blue-purple engorged, knotted, tortuous veins which radiate from the umbilicus across the anterior abdomen [Figure 6]. While typically asymptomatic, bleeding from caput medusae has been described in rare instances.10 In these situations, local wound care with suture hemostasis or use of pressure dressings can temporarily control bleeding, however, variceal hemorrhage will rapidly recur without relief of the underlying portal hypertension.17

Bier spots

Bier spots are another vascular phenomenon which can arise in association with liver disease, occurring secondary to venous stasis from damage to small blood vessels. These small lesions appear on the extremities as irregular, hypopigmented macules typically with a small surrounding halo of erythema [Figure 7]. Bier spots can be differentiated from true pigmentation disorders in that these spots are transient lesions which disappear with pressure or elevation of the affected limb. Bier spots are benign, asymptomatic, and self-limiting.18

Terry’s nails

Terry’s nails were first described in 1954 by Dr. Richard Terry when he observed “white nails” in 82 of 100 consecutive patients with cirrhosis.19 This classic finding can be described as a diffuse ground glass opacity of the nail plate— powdery white at the proximal end with a thin 0.5-3.0mm band of reddening distally [Figure 8]. A recent prospective, cross-sectional observational study by Nelson et al. found Terry’s nails to be ten times more common among inpatients than outpatients, suggesting a positive correlation with disease severity. They also found the sign to be highly specific— up to 98%— for cirrhosis among outpatients, which is important to note for any physicians regularly seeing patients in the office setting.20 There is no specific treatment for Terry’s nails.

Hepatitis B

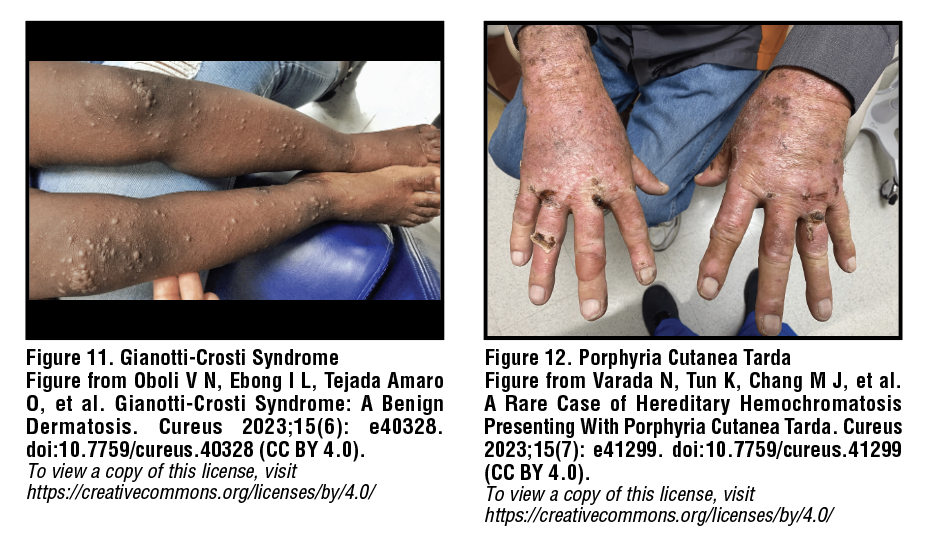

Serum sickness-like reaction

A serum sickness-like reaction (SSLR) occurs in 10-20% of patients with acute hepatitis B (HBV) in the preicteric phase, making it the most common associated cutaneous manifestation. Symptoms of SSLR can include fever, malaise, synovitis and edema of joints, and dermatologic findings such as urticaria and maculopapular rash [Figure 9]. Urticarial lesions are intensely pruritic, well-circumscribed, raised, skin-colored wheals with or without surrounding erythema that may involve concurrent angioedema. Deposition of immune complexes is pathogenic in HBV, with histopathology revealing small vessel vasculitis with direct immunofluorescence positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), IgG, IgM, and C3.21 While SSLR has been associated with acute HBV infection, it has also been noted in rare cases following hepatitis B immunization.22,23 For mild to moderate rash and pruritis, symptomatic relief can be achieved with NSAIDs and/or antihistamines. For more severe symptoms, a 7 to 10-day course of systemic glucocorticoids can be helpful.24

Polyarteritis nodosa

It is estimated that 20% of patients with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) are infected with hepatitis B, and approximately 7% of patients with acute hepatitis B infection go on to develop PAN. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa involves inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels, likely related to deposition of antigen-antibody complexes including hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) within vessel walls. Notably, HBV-associated PAN is not typically associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), unlike other small vessel vasculidities.25 Lesions are most common on pressure points such as the lower legs, back of the foot, and knees. Lesions begin as small, tender nodules with overlying erythema and may progress to larger, ulcerating inflammatory plaques. PAN can also be associated with palpable purpura from small vessel vasculitis or ecchymoses and blood-filled vesicles due to cutaneous infarction [Figure 10]. Treatment for cutaneous PAN includes short-term oral corticosteroid therapy followed by antivirals and plasmapheresis.26

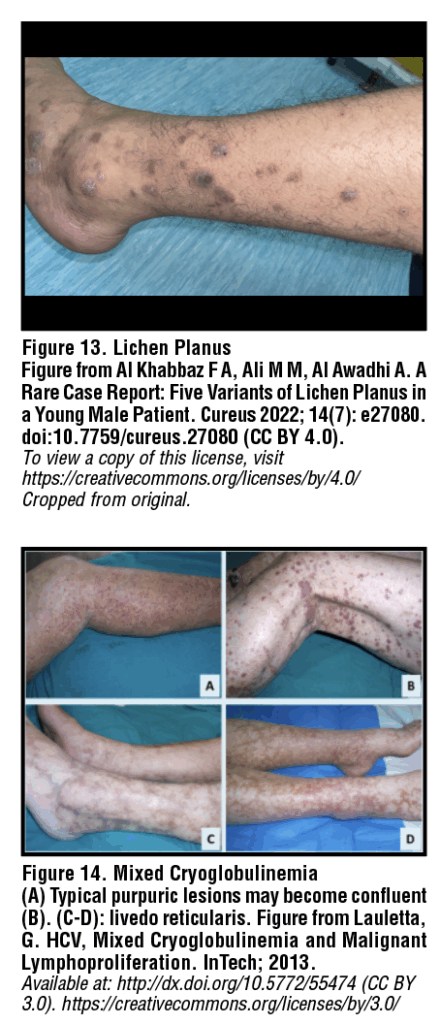

Papular acrodermatitis of childhood

(Gianotti-Crosti syndrome)

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome was first described in 1955 as a manifestation of acute HBV infection, occurring primarily in children up to 12 years of age and rarely in adults. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome is characterized by a symmetric, monomorphic rash consisting of flat-topped, pink-red papules which erupt over the thighs and buttocks and gradually spread to extensor surfaces of the arms and, eventually, the face [Figure 11].27 Patients may also develop vesicular lesions which eventually fade in 2-8 weeks with mild scaling. Post-inflammatory hyper/hypopigmentation may occur in darker skin types and persist for up to 6 months. While the rash is benign and self-limiting, a mild topical steroid, emollient, or oral antihistamine may be used for symptomatic relief of itching.28,29

Table 1. Cirrhosis, Hepatitis, and Associated Dermatologic Manifestations

| Liver Disease | Associated Dermatologic Findings |

| Cirrhosis | Spider angiomata Palmar erythema Paper money skin Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis Caput medusae Bier spots Terry’s nails |

| Hepatitis B | Serum sickness-like reaction Polyarteritis nodosa Papular acrodermatitis of childhood (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome) |

| Hepatitis C | Porphyria cutanea tarda Lichen planus Mixed cryoglobulinemia Necrolytic acral erythema |

Hepatitis C

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is caused by a deficiency of the hepatic enzyme uroporphyrin decarboxylase. As a consequence of this deficiency, excess heme precursors deposit in the skin resulting in cutaneous manifestations from acquired photosensitivity. Visible light activates precursors deposited in the skin, initiating a photochemical reaction which ultimately leads to characteristic skin blistering. Lesions are found on sun-exposed areas such as the face, scalp, and dorsal forearms and hands, and may appear vesicular, scleroderma-like, or manifest as crusted erosions following minor injuries [Figure 12]. Melasma-like hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis may also be observed in the head and neck area. The sporadic form of PCT is significantly associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection as well as chronic alcohol use.23 Management may include sun protection with titanium dioxide or zinc oxide-containing sunscreens, tanning cream containing dihydroxyacetone, and/or protective clothing. Areas of broken skin should be kept clean and any infection addressed promptly. Severe cases of PCT may be treated with iron removal via phlebotomy or antimalarial therapy such as hydroxycholorquine.30

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a chronic mucocutaneous inflammatory disease, most likely involving an immune-mediated reaction. Cutaneous lichen planus lesions can be described using the “Six Ps”: purple, polygonal, planar, pruritic papules and plaques. Lesions are most common around the flexor wrist and ankles, with hallmark signs being intense pruritis and Wickham’s striae: fine white reticulated lines overlying papules or plaques [Figure 13].31 Lichen planus can also affect the oral cavity, with possible involvement of the buccal mucosa, tongue, gums, and lips. Oral lichen planus may display either a white reticular, erosive, or plaque-like pattern. Treatment of lichen planus is primarily symptomatic and may not be required for mild disease. Options include topicals such as potent corticosteroids, tacrolimus ointment, and pimecrolimus cream. Notably, HCV patients with oral lichen planus may be at increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The current literature indicates a greater risk of malignant transformation in HCV patients with oral lichen planus than in those without HCV infection.32,33 Patients should be referred to dermatology for further management and symptom monitoring.34

Mixed cryoglobulinemia

Mixed cryoglobulinemia is the most commonly reported extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection, with studies noting an incidence of HCV in 40-90% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. In HCV patients, cryoglobulins may represent the product of virus-host interactions, as circulating virus acts as a continuous immune stimulus.35 Cutaneous manifestations of mixed cryoglobulinemia are diverse and can include palpable purpura of the lower extremities, Raynaud’s phenomenon (white coloration and numbness of the fingers upon exposure to cold), secondary acrocyanosis (asymmetric, persistent, blue discoloration of fingers or toes), and livedo reticularis (reticular cyanotic pattern with mottling, typically of the lower extremities) [Figure 14]. First-line therapy for HCV-associated cryoglobulinemia is direct-acting antivirals to treat HCV. Rituximab has also been reported to be effective. Finally, patients should be advised to avoid cold environments to prevent triggering precipitation of additional cryoglobulins.36–38

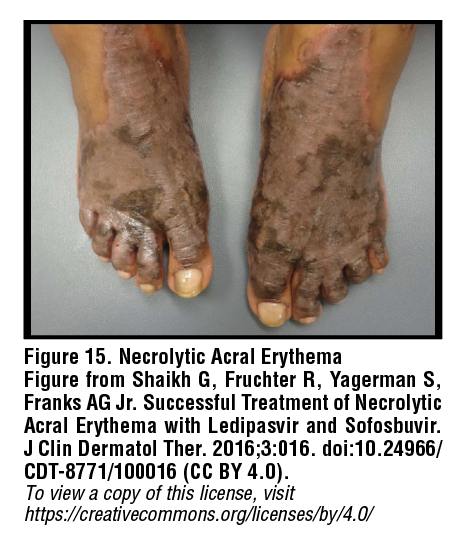

Necrolytic acral erythema

Necrolytic acral erythema (NAE) is a specific cutaneous feature of HCV infection. Notably, all instances of NAE have been documented in Asian or African patients. The etiopathogenesis of NAE appears to be multifactorial and may involve genetic factors and zinc deficiency as well as hypoalbuminemia and hypoglucagonemia as a result of chronic liver dysfunction. NAE presents as a symmetrical acral rash, typically on the dorsal feet, with well-circumscribed dusky discoloration and flaccid blistering which may progress to thick hyperpigmented plaques with adherent scale [Figure 15].39 Oral zinc supplementation and interferon-based regimens can aid in resolution of lesions. Topical treatments do not appear to be efficacious.40

Conclusion

Cirrhosis and hepatitis are associated with a number of extrahepatic manifestations, with dermatologic findings often being the earliest or most readily-identifiable. While most cutaneous findings are not necessarily specific for one condition, constellations of skin lesions with other symptoms can provide important clues to underlying disease processes. For this reason, it is important for general practitioners and dermatologists alike to be able to recognize and describe such lesions. Identification of typical cutaneous lesions in liver disease can lead to earlier diagnosis, reduction of unnecessary spending, and prompt treatment initiation.

References

1. Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):151-171. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.09.014

2. Kochanek KD. Mortality in the United States, 2022. 2024;(492).

3. Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Leading Causes of US Deaths in the 2022. J Clin Med. 2024;13(23):7088. doi:10.3390/jcm13237088

4. Ma C, Qian AS, Nguyen NH, et al. Trends in the Economic Burden of Chronic Liver Diseases and Cirrhosis in the United States: 1996–2016. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(10):2060-2067. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001292

5. Nath P, Anand AC. Extrahepatic Manifestations in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 2022;12(5):1371-1383. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2022.02.004

6. Bhandari A, Mahajan R. Skin Changes in Cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 2022;12(4):1215-1224. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2021.12.013

7. Li CP, Lee FY, Hwang SJ, et al. Spider angiomas in patients with liver cirrhosis: role of alcoholism and impaired liver function. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(5):520-523. doi:10.1080/003655299750026272

8. Li CP, Lee FY, Hwang SJ, et al. Spider angiomas in patients with liver cirrhosis: role of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(12):2832-2835. doi:10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2832

9. Silvério A de O, Guimarães DC, Elias LFQ, Milanez EO, Naves S. Are the spider angiomas skin markers of hepatopulmonary syndrome? Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50(3):175-179. doi:10.1590/S0004-28032013000200031

10. Liu Y, Zhao Y, Gao X, et al. Recognizing skin conditions in patients with cirrhosis: a narrative review. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):3017-3029. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2138961

11. Satoh T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Vascular spiders and paper money skin improved by hemodialysis. Dermatology. 2002;205(1):73-74. doi:10.1159/000063136

12. Serrao R, Zirwas M, English JC. Palmar erythema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8(6):347-356. doi:10.2165/00128071-200708060-00004

13. Matsumoto M, Ohki K, Nagai I, Oshibuchi T. Lung traction causes an increase in plasma prostacyclin concentration and decrease in mean arterial blood pressure. Anesth Analg. 1992;75(5):773-776. doi:10.1213/00000539-199211000-00021

14. Waqar MU, Cohen PR, Fratila S. Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis (DSAP): A Case Report Highlighting the Clinical, Dermatoscopic, and Pathology Features of the Condition. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26923. doi:10.7759/cureus.26923

15. Santa Lucia G, Snyder A, Lateef A, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Topical Lovastatin Plus Cholesterol Cream vs Topical Lovastatin Cream Alone for the Treatment of Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(5):488. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0205

16. Philips CA, Arora A, Shetty R, Kasana V. A Comprehensive Review of Portosystemic Collaterals in Cirrhosis: Historical Aspects, Anatomy, and Classifications. Int J Hepatol. 2016;2016:6170243. doi:10.1155/2016/6170243

17. Chen PT, Tzeng HL, Wang HP, Liu KL. Caput Medusae Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(10):1570-1570. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000000542

18. Peyrot I, Boulinguez S, Sparsa A, Le Meur Y, Bonnetblanc JM, Bedane C. Bier’s white spots associated with scleroderma renal crisis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(2):165-167. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02298.x

19. Terry R. White nails in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet. 1954;266(6815):757-759. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(54)92717-8

20. Nelson N, Hayfron K, Diaz A, et al. Terry’s Nails: Clinical Correlations in Adult Outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1018-1019. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4441-7

21. Neumann HA, Berretty PJ, Folmer SC, Cormane RH. Hepatitis B surface antigen deposition in the blood vessel walls of urticarial lesions in acute hepatitis B. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104(4):383-388. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1981.tb15307.x

22. Gupta R, Fakunle I, Samji V, Hale EB. Serum Sickness-Like Reaction Associated With Acute Hepatitis B in a Previously Vaccinated Adult Male. Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14742. doi:10.7759/cureus.14742

23. Cozzani E, Herzum A, Burlando M, Parodi A. Cutaneous manifestations of HAV, HBV, HCV. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156(1). doi:10.23736/S2784-8671.19.06488-5

24. Clark BM, Kotti GH, Shah AD, Conger NG. Severe serum sickness reaction to oral and intramuscular penicillin. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(5):705-708. doi:10.1592/phco.26.5.705

25. Trepo C, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa and extrahepatic manifestations of HBV infection: the case against autoimmune intervention in pathogenesis. J Autoimmun. 2001;16(3):269-274. doi:10.1006/jaut.2000.0502

26. Guillevin L, Mahr A, Callard P, et al. Hepatitis B virus-associated polyarteritis nodosa: clinical characteristics, outcome, and impact of treatment in 115 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84(5):313-322. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000180792.80212.5e

27. Dikici B, Uzun H, Konca C, Kocamaz H, Yel S. A case of Gianotti Crosti syndrome with HBV infection. Adv Med Sci. 2008;53(2):338-340. doi:10.2478/v10039-008-0013-0

28. Fergin P. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Non-parenterally acquired hepatitis B with a distinctive exanthem. Med J Aust. 1983;1(4):175-176. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1983.tb104350.x

29. Lee S, Kim KY, Hahn CS, Lee MG, Cho CK. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome associated with hepatitis B surface antigen (subtype adr). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1985;12(4):629-633. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(85)70085-0

30. To-Figueras J. Association between hepatitis C virus and porphyria cutanea tarda. Mol Genet Metab. 2019;128(3):282-287. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.05.003

31. Asaad T, Samdani AJ. Association of lichen planus with hepatitis C virus infection. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25(3):243-246. doi:10.5144p/0256-4947.2005.243

32. Gandolfo S, Richiardi L, Carrozzo M, et al. Risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma in 402 patients with oral lichen planus: a follow-up study in an Italian population. Oral Oncol. 2004;40(1):77-83. doi:10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00139-8

33. Gheorghe C, Mihai L, Parlatescu I, Tovaru S. Association of oral lichen planus with chronic C hepatitis. Review of the data in literature. Maedica (Bucur). 2014;9(1):98-103.

34. Pelet Del Toro N, Strunk A, Garg A, Han G. Prevalence and treatment patterns of lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online November 22, 2024:S0190-9622(24)03236-5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.09.081

35. Lauletta G, Russi S, Conteduca V, Sansonno L. Hepatitis C virus infection and mixed cryoglobulinemia. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:502156. doi:10.1155/2012/502156

36. Lunel F, Musset L, Cacoub P, et al. Cryoglobulinemia in chronic liver diseases: role of hepatitis C virus and liver damage. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(5):1291-1300. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(94)90022-1

37. Schamberg NJ, Lake-Bakaar GV. Hepatitis C Virus-related Mixed Cryoglobulinemia: Pathogenesis, Clinica Manifestations, and New Therapies. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(9):695-703.

38. Yokoyama K, Kino T, Nagata T, et al. Hepatitis C Virus-associated Cryoglobulinemic Livedo Reticularis Improved with Direct-acting Antivirals. Intern Med. 2023;62(24):3631-3636. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.1671-23

39. Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2):247-251. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.049

40. Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136(6):755-757. doi:10.1001/archderm.136.6.755

Olivia Babich

Olivia Babich Alexandra Savage

Alexandra Savage